11.05 | Permission to Cry Over Pasta: They don't hate your guts, they're just Italian.

Reflections on rejection, and why it hurts so much. Also, are you mad at me?

Hi.

Are you mad at me?

For years, this question circulated constantly in my mind, riding on the news ticker at the bottom of my brain’s newscast most hours of the day.

I eye the barista at Saint Espresso in Kentish Town, London, where I’ve decided to work on my laptop for the day, mooching off their free Wi-Fi and available outlets. The cafe is nearly empty on this rainy Tuesday morning. I’ve ordered a matcha latte (I’m once again off the coffee train after a caffeine-induced panic in Italy) and have mentioned at least twice that I’ll be ordering something for lunch in a few hours. The barista hasn’t at all indicated that I’m inconveniencing him or the cafe at large.

And yet.

Is he mad at me?!

I shoo away the question. I’ve been trying consciously to resist bending to its power for about a month now, ever since a silly incident during my first week in Italy highlighted how deeply rooted it is within my psyche. It’s still there, occupying prominent space on said news ticker. But I’m not as fixated on it these days. Here’s why.

I stood in an alleyway, my heart pounding.

On a balmy September evening in Rome, I walked to a restaurant on the outskirts of Trastevere high on my list for excellent cacio e pepe a few minutes after Google Maps said it opened. It was my second night alone in Rome, and I wanted the first pasta noodle I tasted in Italy to be slathered in cheesy, peppery goodness. I rehearsed my Italian inquiry for a table for one and greeted the host.

Chloe: Buonasera. Possi avere un tavolo, per favore? Sono solo io.

Host, responding in perfect English: No, I am afraid we are fully booked this evening.

Chloe, nervously: I’m just one person. I will be quick!

Host, firmly: No, come back another time with a reservation.

I thanked him profusely for nothing and walked to another nearby restaurant, where a similar exchange unfolded. Upon hearing that second brisk “no,” something strange happened.

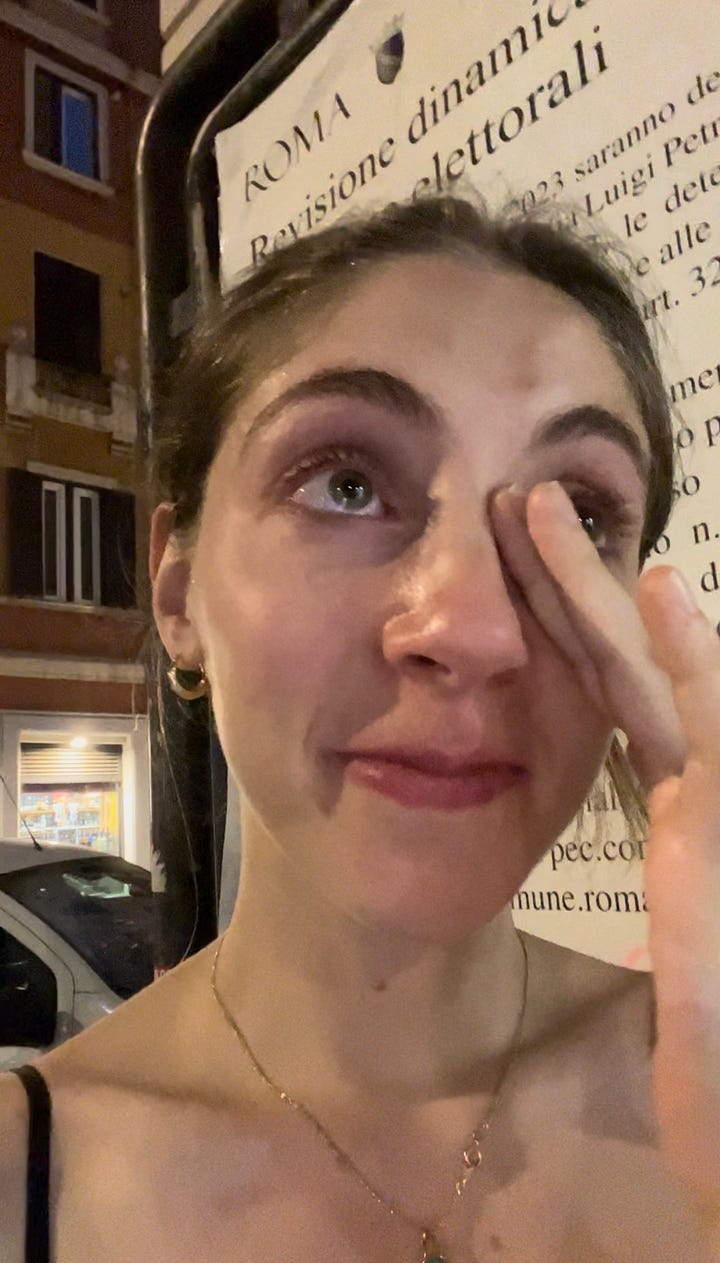

Tears flooded my eyes. Embarrassed, I apologized to the host and walked out onto the street. Fat, salty tears spilled down my cheeks as I started away from the restaurant. I wiped them away, confused.

Why am I crying? I wondered, speed-walking away from sidewalk tables overflowing with people enjoying aperitivo. I don’t care this much about pasta. And the host wasn’t mean. He was direct, as most Italians are.

When I’m dealing with uncomfortable feelings, I sometimes talk to myself over video or voice memo. It’s a bizarre form of self-voyeurism that I find kind of therapeutic; it gets my thoughts out of my head, which in turn allows me to hear them more objectively.

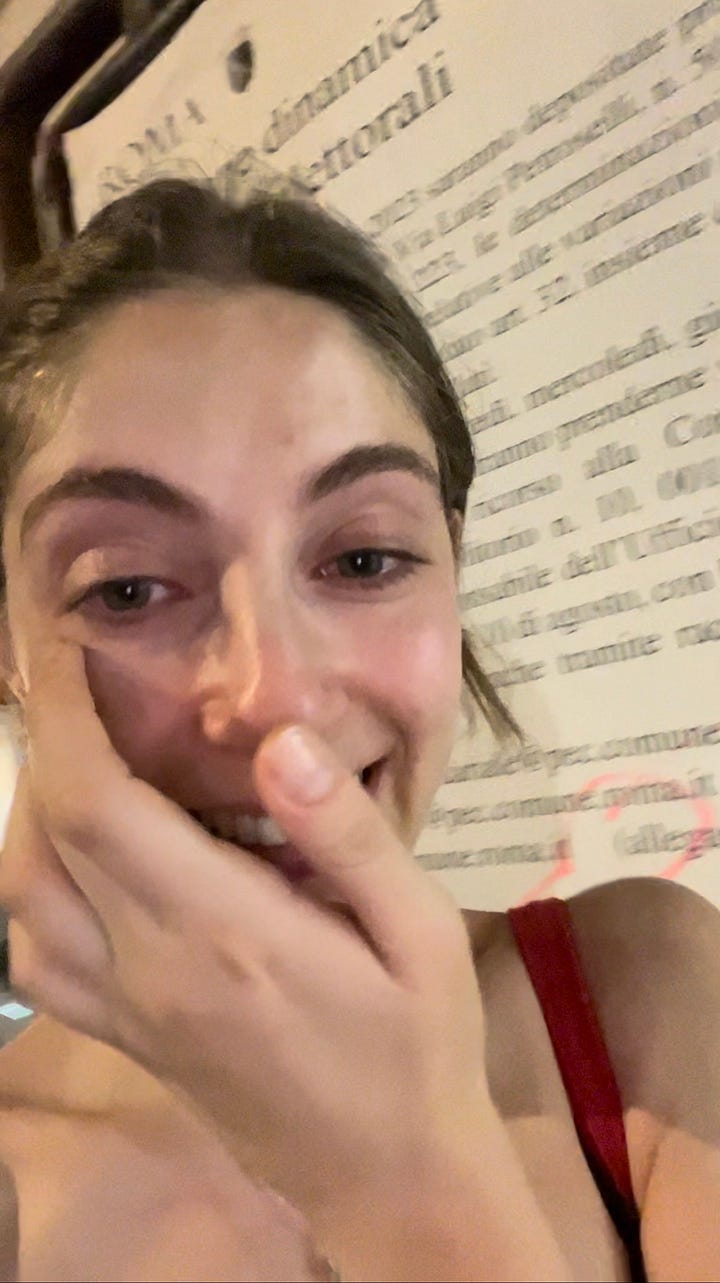

I turned my iPhone camera on myself and hit “record.” I giggled at how ridiculous I felt, recording myself crying over something so unbelievably silly.

“I’m just laughing at how fragile my ego is,” I say, rolling my eyes at my reflection. “People politely declining me makes me upset, even though it has nothing to do with me.”

At hearing that, my smile turns into a frown, and my eyes once again grow watery. I feel ridiculous admitting that I actually choked back a sob (a sob!! I can see the headline now: Amid Global Wars and Real Tragedy, White Girl Traveling Around Europe Sheds Tears Over One Bowl of Pasta).

“I’m so sensitive to rejection,” I say, wiping my eyes in wonder. I was now attracting stares from a few curious passersby. I paused my rambling and smiled creepily at them between alternating sobs and giggles, ever committed to upholding the esteemed reputation of Americans abroad. Once they were out of earshot, I returned to my personal broadcast.

“It’s just indicative of how personally I take rejection of all kinds,” I add. “It’s ridiculous, I know.”

My mind turned to my fellowship. “How to Cope with Rejection” should have been taught as a course in the master’s program I completed last year at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. Over the course of the last few months, I’d started reporting several freelance stories, pitching them before moving onto a new idea when I didn’t receive replies to the few emails I’d sent. This very unproductive cycle left me with deep feelings of inadequacy and shame, plus a bunch of half-reported stories I’d started and abandoned before finishing. Now, I’m nearing the point of pitching my big story I’ve been working on for the last two months. And I’m terrified. What happens if no one wants to publish it?

A woman speaking Italian loudly into her phone jolts me out of my anxious spiral. “This fear of rejection holds me back so much,” I tell the camera. I conclude my selfie video with a hopeless shrug before heading in the direction of a new restaurant.

When the weekend approached, I reunited with some of my closest friends (more on our trip in my last two posts, here and here!) I opened up to them about how I’d been feeling: anxious that I hadn’t yet published anything, embarrassed by my sensitivity to rejection, and ashamed by how much it all was holding me back. My friends lovingly bandaged my emotional wounds with compassion and encouragement. And I felt better. Until Monday arrived and I was on my own again, ruminating on the same limiting thoughts as before.

Research suggests that the area of our brain that’s activated by physical pain lights up when we experience rejection. So, rejection — even the gentlest of letdowns — actually hurts. But what happens once the pain subsides?

In the wake of failure or rejection, why is it so hard for us to treat ourselves with the same kindness we reserve for our friends and loved ones?

It’s because we don’t know how to practice emotional hygiene, says psychologist Guy Winch. “Especially after a rejection, we all start thinking of all our faults and our shortcomings, what we wish we were, what we wish we weren’t, we call ourselves names,” Dr. Winch says in his 2015 TedTalk. “Our self-esteem is already hurting. Why would we want to go and damage it further? We wouldn’t make a physical injury worse on purpose. You wouldn’t get a cut on your arm and decide, ‘oh I know! I’m going to take a knife and see how much deeper I can make it.’ But we do that with psychological injuries all the time.”

Dr. Winch builds a compelling argument on the importance of taking care of our emotions with the same attention and diligence we use to take care of our bodies. The first thing we must do when we get rejected, he says, is revive our self-esteem. If we don't, our minds will try to convince us that we’re incapable, or unworthy.

“That’s why so many people function below their actual potential,” he says. “Because somewhere along the way, a single failure convinced them they couldn’t succeed, and they believed it.”

The people who succeed in life aren’t those who are somehow immune to failure — they’re just the ones who keep trying. Practically every success story in history was preceded by generous helpings of rejection. Here are a few famed ones that might surprise you:

Meryl Streep was called too “ugly” for a film role.

Michael Jordan was cut from his high school basketball team.

Thomas Edison’s teachers told him he was “too stupid to learn anything.”

Stephen King’s first novel was rejected by over 30 publishing houses.

Walt Disney was fired from a local newspaper because his editor said he lacked imagination.

Oprah Winfrey was told she was “unfit for television news” and lost her first anchor job.

If these once-ordinary people didn’t practice the basic emotional hygiene necessary to pick themselves up and try again after facing rejection, we wouldn’t know their names today.

Back in Rome, my stomach rumbled. I took a few laps around a nearby piazza, wandering at last into a random trattoria whose name I did not recognize from any “must eat” lists I’d bookmarked from the internet. The restaurant was nearly empty at 8:00 p.m., but the host was kind and welcoming. There, I finally had my first bite of pasta in Rome: not a swirled forkful of tonnarelli cacio e pepe, but a simple square raviolo stuffed with spinach and ricotta.

That bowl of ravioli remains one of my better meals in Rome. And, to be honest, it outranks every pasta cacio e pepe I tried over the course of the week.

The silly story of how I found myself crying alone on a side street in Rome is one that makes me laugh today. But more importantly, it reminds me to actively practice emotional hygiene in the face of rejection. Instead of wasting minutes wondering if the Italian waiter who rolled his eyes and imitated my weak pronunciation of tagliatelle to his colleague hates my guts, or if the friend who didn’t like my latest Instagram post is secretly furious with me, or if editors passing on my pitches means I should give up on publishing my writing altogether, I’ve been trying to build myself up. I’m a cute American girl who gave those waiters a laugh, I tell myself. My self-worth isn’t determined by double-taps on a glowing screen. Being rejected means I tried, and that’s worth celebrating. And I’ll try again.

After all, an even better bowl of pasta might be right around the corner.

How do you pick yourself up after facing rejection? I’d love to know.

Thank you so much for reading. As always.

Love,

Chloe

I love your writing , you are so funny but real. I think you should write a novel,it would be a huge success.xxoo

"I paused my rambling and smiled creepily..." 😂 Made me laugh out loud.