10.17 | Permission to Observe: Yom Kippur in Rome's Jewish Ghetto

This one's for the history buffs: A glimpse into the oldest Jewish community in Europe, and an inspiring story of light in a time of darkness.

Church bells tolling in the distance announce the time: It’s noon. I’m on Ischia, an island off Naples, Italy, reunited with my parents and brother about halfway through my time abroad for my fellowship. We’re here on holiday, but as we lounge seaside and enjoy steaming forkfuls of spaghetti alla vongele, we’ve been mostly silent, eyes glued to our phones, consuming the horrific news of Hamas’s unprecedented terrorist attack on Israel and what it’s meant for thousands of innocent civilians in Gaza, as well as the spike in anti-Semitism it’s inspired globally.

My time in Italy started with a weekend in Rome spent with some of my dearest friends. Kacy Fishman is one of them; she joined us for the weekend from Tel Aviv, Israel, where she lives and remains today. The Nova Music Festival where over 250 concertgoers were massacred could have very well been a nature party she chose to attend. In the days since Hamas’s initial attack, Kacy has raised thousands of dollars to purchase supplies to help those caught in the crossfire and fighting on the front lines. Over a week later, there is still immense need for help, so she’s continuing her fundraising effort. If you’re interested, you can donate via Venmo: Her account is @Kacy-Fishman. If you don’t have a Venmo account, feel free to reach out to me, and I can send her money on your behalf. 100% of your contribution will go towards aid.

There are so many other ways to help. Here are a few worthy causes I plucked from this spreadsheet and this NPR roundup:

The software investment company Insight Partners is matching donations to several humanitarian aid groups up to $1 million. Another one of my dear friends, Eugenia Lustgarten, works here; she’s confirmed that they have yet to reach their goal. To compound your donation, consider contributing here.

Similarly, Michael Bloomberg is matching donations to Magen David Adom, the Israeli Red Cross. You can make a matched donation here.

The International Committee of the Red Cross is working with Magen David Adom and the Palestine Red Crescent Society to provide medical assistance to those wounded and in need. Consider donating here.

Donate directly to the affected Kibbutzim: Kibbutz Kfar Azza, Kibbutz Nir Oz, Kibbutz Be’eri were among the most impacted, and have corresponding fundraisers. In total, 23 Kibbutzim along the Gaza border were affected by the attacks; you can donate to these Kibbutzim at large here.

Anera (American Near East Refugee Aid) is working to support displaced families in Gaza and support medical personnel on the ground. $30 can provide the Central Blood Bank Society in Gaza with 16 blood bags. You can donate here.

After my friends left Rome, I extended my stay to learn about the Jewish Ghetto and observe Yom Kippur. That’s what this post will cover. Especially if you’re not Jewish, I think you’ll be able to learn something valuable from it. I’m particularly proud of this one. Thank you for sticking with me!

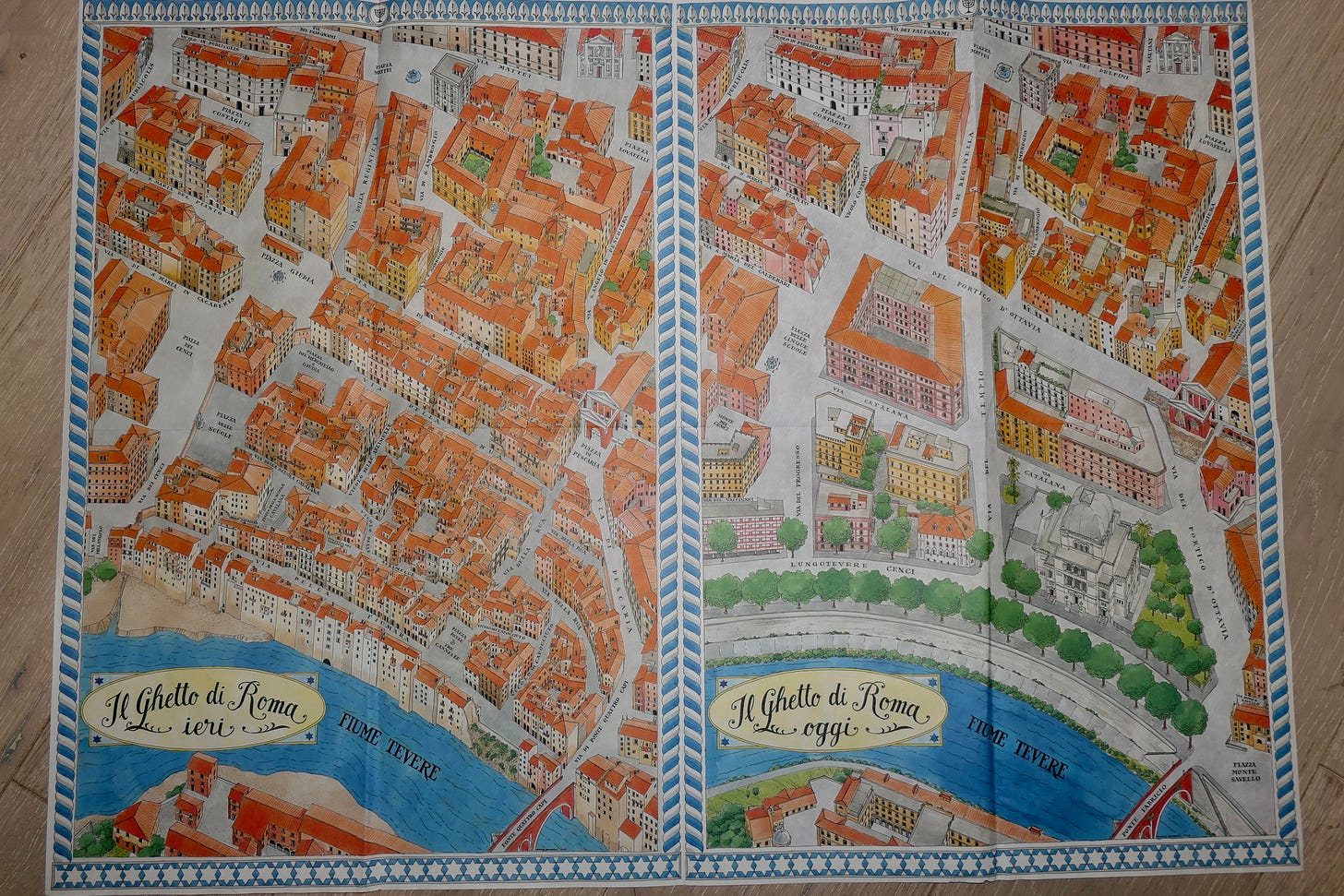

Editor’s Note: Much of the information I gathered came from 1) an informational pamphlet and map I picked up at a Jewish bookstore in the ghetto and 2) conversations with Micaela Pavoncello, my excellent Roman Jewish tour guide; if not otherwise cited, the facts below are from these sources.

A brief history of Rome’s Jewish Ghetto

Jews first arrived in Rome before Caesar ruled. During his reign, Caesar granted religious freedom and protection to the city’s Jewish community as a show of gratitude for the critical military assistance Jews living in Judaea (modern-day Israel) provided during a key battle in Egypt. In an excerpt from “Julius Caesar: The People’s Dictator,” Luciano Canfora writes, “Caesar owed his salvation to the Jews, and this he never forgot.” Many Roman Jews allegedly attended the leader’s funeral.

Jews have lived in Rome for over 2,000 years, longer than in any other European city. The majority of that time was marked by severe discrimination, led by the posture of the Papacy. In 1555, Pope Paul IV established Rome’s Jewish Ghetto with the papal bull “Cum Nimis Absurdum,” which, when translated, suggests that he found it absurd for the Jews to consider themselves equal to the Catholics and live in the same community.

Today, a visit to the Jewish Ghetto is listed as a top activity for tourists exploring the city of Rome. For many, that looks like a quick stroll followed a taste of Carciofi alla giudia, artichoke fried in the signature Jewish style. Visitors swarm the ghetto’s winding streets, snapping photos of charming old signs and weathered statues without learning their true history. At first, I did the same. Only after I joined an excellent tour led by Roman Jew Micaela Pavoncello did I understand that the “ghetto” I walked around barely resembled the ghetto of centuries ago, overflowing with tenement-style buildings erected on the shore of the Tiber River that flooded each winter as the river rose. Today, those waterlogged buildings are gone, and the area is now protected by a sturdy embankment lined with sweeping trees.

Micaela Pavoncello has been leading tours in Rome for over 20 years. “The Jewish history cannot be just confined in the bite of an artichoke,” she said. Over lunch at Renato al Ghetto, a kosher restaurant in the heart of the ghetto, Micaela lamented the thousands of tourists who frequent the ghetto without understanding its rich history. “They miss our point of view,” she explained between mouthfuls of antipasti. “It’s ignorance, not anti-Semitism.”

The history of Rome’s Jewish Ghetto, the second-oldest in the world (predated by the Jewish Ghetto in Venice, formally established in 1516) is a sad one, full of oppression and discrimination. Jewish men and women couldn’t leave the ghetto during the day without wearing yellow, to distinguish themselves from non-Jews and to enforce further shame, as the color yellow was associated with prostitutes at the time. Overcrowding in the ghetto caused diseases to spread rapidly. When the Naples Plague hit in 1656, nearly a quarter of the ghetto’s population died.

With the creation of the ghetto in 1555, Jews went from working as prominent doctors and lawyers to selling rags. Most trades were forbidden to Jews, with the exception of three undesirable jobs: money-lending, a profession forbidden to Christians; fish-mongers; and fabric peddlers. Over the centuries, Jewish textile workers honed their craft to create intricate mappot, or fabric Torah coverings, which are now displayed proudly in the Jewish Museum in Rome.

For years, Jews were forced to take part in the palio degli ebrei, or “race of the Jews,” a humiliating series of competitions along Rome’s main street during Carnival celebrations ahead of Lent. Citing the Medici Archives, an entry on the Jewish Currents website elaborates:

“at one point, Christian ‘jockeys’ in the race rode Jews instead of horses. Another festive ‘game’ . . . was to roll a Jew in a nailed barrel down the Testaccio Hill. . . . By the 1580s, the Jews are known to have run the race naked.”

But the story of the ghetto is also one of remarkable resilience. When Jews were forced to attend Catholic Mass on Shabbat, they plugged their ears with wax. There was only one synagogue permitted to be erected in the ghetto to serve Rome’s diverse Jewish population, so the Jews built out five different mini-synagogues under one roof so they could celebrate different rites. When a papal decree forbade Jews from selling dairy products, Jewish bakers started concealing the ricotta filling of their crostata beneath a blackened crust. You can still find this variation today at Pasticceria Boccione, the oldest surviving kosher bakery in the ghetto.

In the Piazza Mattei in the center of the former ghetto, you can’t miss the Fountain of Turtles, or Fontana delle Tartarughe, which dates back to 1588. Local legend has it that the artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini added the iconic turtles to the basin of the now aptly-named fountain in 1658 to pay homage to Rome's Jews, ancient and resilient like the hard-shelled reptiles.

Micaela’s father comes from a long line of Jews in Rome. “Roman Jews are the most ancient Romans,” Micaela said. She gestured to herself. “We never left.”

A story of light in darkness: Gold for the Nazis

I covered my shoulders with a scarf and entered the church-like Tempio Maggiore, the Great Synagogue, which was triumphantly erected nearly 125 years ago on the border of the former ghetto. I sat in the wooden pews with the rest of the tour group and listened as Micaela told a story from 80 years ago that gave me goosebumps.

With the unification of Italy and the dissolution of the Papal States in 1870, Roman Jews finally obtained equal rights. The ghetto’s walls were torn down in 1888, and Jews assimilated back into Roman society. But this period of freedom was short-lived.

Rome fell to Nazi occupation in the summer of 1943. Herbert Kappler was placed in charge of Jewish roundups for deportations to Auschwitz. On September 26, Kappler summoned prominent Jewish-Italian leaders to his headquarters, where he threatened to deport 200 Jewish heads of household if they did not bring him 50 kilograms of gold within 36 hours.

Immediately, Romans of all backgrounds sprung to action.

Catholic women unclasped gold necklaces from their necks.

Men tossed in their wedding bands.

Micaela grew emotional as she recounted how even the poor non-Jewish woman who sold snacks on the street outside the nearby cinema contributed something. “The Roman modest people shared the little that they had to save their brothers,” she said. In a remarkable show of unity in the height of anti-Semitic persecution across Europe, Romans came together in an attempt to save their neighbors’ lives.

On September 28, an hour before the deadline, a sealed box with 50 kilograms of gold scraped together from the citizens of Rome arrived at Kappler’s office. That evening, the box was put on a train to Berlin, addressed to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the head of the Reich Security Main Office.

Most Jews believed that, having obtained the gold, the Germans would spare their lives. They didn’t think there would be deportations from Italy, least of all from Rome, where they felt their proximity to the Pope provided an extra layer of protection.

But two weeks later, on a rainy morning on the Jewish day of rest, the Nazis raided the Jewish quarter. Even then, many non-Jews actively resisted the roundup. Kappler’s correspondence includes an instance where, an hour before the roundup, an Italian took over a Jewish household in Rome and insisted it was his; the letter also describes how some individuals waved their own pistols in attempts to hold policemen back from the Jews.

Still, 1,259 people were captured. The 200 who were not considered purely Jewish were freed, and the remainder were taken to Auschwitz two days later. Of those people, only 16 survived: 15 men and one woman.

After the war, the box of gold the Roman community had collected was found in Kaltenbrunner’s office. It had never even been opened.

This story has remained in my mind for weeks and feels especially relevant to share today. The Roman community’s heroic effort to collect the gold technically didn’t save any lives; the ultimatum was a cruel trick played by the Germans who planned to proceed with the roundup regardless. But the story embodies the unity that was possible during a time of darkness. I’m inspired by the generosity and courage of ordinary Romans willing to help the Jews, a population they had been conditioned to “other” for centuries. Like the woman who peddled snacks outside the cinema in Rome, we all have something we can spare for those in need.

An American Jew walks into an Italian synagogue

At the end of our tour, Micaela opened the floor to questions. “It’s not easy to find a Roman Jew, you better take advantage,” she said, wagging her finger. Someone asked where Roman Jews fall within the three main branches of Judaism: Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. Micaela’s answer: None of the above!

“Roman Jews are Orthodox in structure, Conservative in philosophy, Reform in behavior, and Catholic in religion,” Micaela said with a wink.

She gestured to her capri pants; the typical Orthodox Jewish woman wears only skirts and dresses. Most Jewish-owned shops in Rome stay open on Saturdays. “If you have to survive in the schmatta (fabric) business, you cannot close your store on Shabbat,” Micaela explained. Upon entering a synagogue, Roman Jews perform a gesture with their hands reminiscent of Catholics making the sign of the cross when entering a church.

The Tempio Maggiore itself looks more like a church than any synagogue I’ve been to. It’s massive, with soaring vaulted ceilings topped with a square dome, the only one of its kind in Rome. As I approached the synagogue’s entrance on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, my stomach turned. Yes, it was already growling in anticipation of a day without food (in my own observation of the holiday, I always drink a little water. Sue me!), but I felt something else: fear.

I worried about sitting or standing when I wasn’t supposed to, or doing something to offend worshippers on this important holiday. The service I planned to attend reflects the Orthodox Italki rite, as practiced by Italian Jews since early Roman times. I’m an Ashkenazi American Jew who can barely speak or understand Italian. Plus, my ability to read Hebrew has faded over the years since my bat mitzvah. Would I even be let in?

I gave myself permission to try. I went through the building’s security check and was pointed to the stairs leading to the women’s section. I grabbed a prayer book and sat towards the back, where I observed the women around me.

They wore t-shirts and jeans, outfits I wouldn’t dare wear to my family’s Conservative synagogue. I suddenly felt overly formal in the long sheath dress I’d dug up from the bottom of my suitcase. As the hours passed, women filed in, clustering around their elderly matriarchs in reverence. It looked like everyone knew each other. They kissed, once on each cheek, and whispered to each other in Italian before settling into prayer.

I wondered how many of these women were children and grandchildren of the 16 Roman Jews who survived Auschwitz. I thought about the ancestors of these women, many of whom likely spent their entire lifetimes confined in the ghetto. I marveled at our privilege to sit and worship freely today.

As I suspected, I barely understood a word of the service. But that evening, as I speed-walked away from the synagogue and toward my favorite non-kosher pizzeria in the ghetto to break my fast, I was overcome with gratitude. I felt lucky to experience the holiday from a new vantage point. I’d gained a newfound appreciation for the collective Jewish spirit of resilience.

And most of all, I was grateful to be ending my Yom Kippur fast in the culinary capital that is Rome with the BEST pizza on planet Earth.

Praying for peace,

זהבה ישראלה

Zahava Yisraela

(This is my Hebrew name, given to me a few days after I was born. It translates to “Golden Israel.”)

Thank you for the history, the suggestions for ways to help, and for sharing your trip - I love your writing. XX

Woman, you have done it again. I have tears in my eyes as I read your beautiful words. I want to think that I would be one of the Catholic ladies who throws in my golden chain. So much suffering in this world, but also, so much courage. Thank you for the history lesson and the reminder that we all need to care for one another. sending love.